by Bharath

This feature story is part of a series covering organisations and collectives working with the underprivileged populations of Thiruvananthapuram and South Kerala.

The year was 1996. An Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led BJP government had won the general elections, albeit lasting only 13 days – the shortest-ever period in Indian politics. The cricket world cup was co-hosted by India and witnessed one of the most controversial and anti-climactic ends in Indian cricket history. Other significant events happened in India and across the globe, as they did every year before that and after.

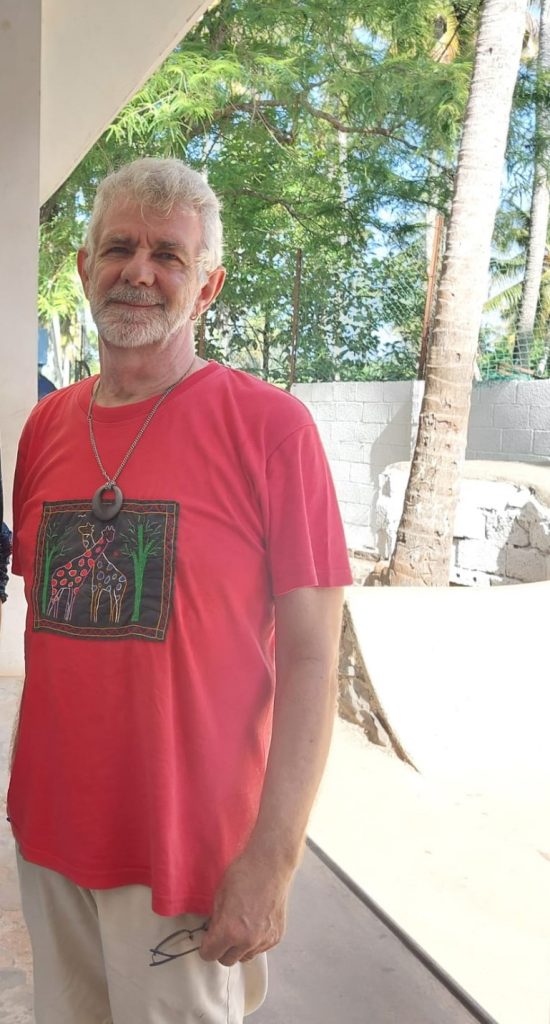

But more contextually, Paul van Gelder visited India for the first time in 1996 and S.I.S.P. was born.

I met Paul for the first time, on a regular Kerala blistering summer noon in May. The S.I.S.P. centre at Kovalam was not the easiest to reach for a direction-disoriented soul like me, but the good local folk guided me. “Skating club, alle? Yes, yes,” some of them remarked knowingly as they helped me with the directions. We sat down at his office for our first conversation, as his cat and dog appraised me from close quarters.

Founded in 1996 by Paul van Gelder and Werner Fynaerts, Sebastian Indian Social Projects (S.I.S.P.) is a non-profit organisation working with the socio-economically disadvantaged communities and populations in the coastal villages from Vizhinjam to Poovar. While S.I.S.P. has focused predominantly on the education of the children, it also closely works with the people in providing healthcare and social & economic empowerment.

In the Beginning, There Was Light

Paul had been a social worker in Belgium for many years, working with people suffering from addiction issues as well as those affected with severe physical disabilities. He also co-owned a Bed & Breakfast – Café in Mechelen. Paul’s visit to Kerala, and Kovalam, was quite serendipitous. He had travelled to meet his brother who was working in Chennai at the time. The city was going through one of its notorious monsoons, rendering it impossible for them to get any outdoor action. The beaches of Thiruvananthapuram, Kovalam in particular, seemed the next popular choice. A place where Paul would spend the major part of his life since.

Life in and around Kovalam and Vizhinjam, like most tourist destinations in India, was a paradox nestled inside a bubble of ironies, Paul and Werner soon realised. Its primary identity had been stamped as an “exotic travel spot” so firmly, that the condition and the challenges of the coastal communities and the migrant population were invisible to the outside world.

They started offering the children basic classes in alphabets and numbers – under the shades of the trees lining the beach. But, they both felt that something more had to be done beyond a token act of service. They decided to utilize the profits of their business venture back in Belgium towards that. The first step was to rent a small building at Kovalam and set up an educational base for the children.

On December’ 6, 1996, Paul and Werner conducted the first class with just a handful of students – marking the birth of S.I.S.P.

“It was just the two of us managing everything at first. Soon we had a team of four teachers. We struck a deal with the children’s parents to send them to school – classes in the morning followed by lunch later,” Paul recollects.

The initial phase was certainly a struggle for them, adapting to the new culture and surroundings, combined with the shuttle back and forth between Kerala and Belgium. While Paul can laugh at it now, he recounts learning the hard way very early on that the local food could be too spicy for his stomach. Ironically, Paul remembers that communication wasn’t as big an issue as he had thought – owing to the thriving tourism culture in the region. But he certainly needed the help of a local translator while visiting further inside the pockets of the coastal villages.

Their efforts were certainly making an impact, evidenced by an increasing number of visits from fishermen who wished to learn to read and write. Within a matter of time, these new students expressed their desire to bring along their mothers and sisters too.

Paul reflects that it was glaringly obvious even back then, that the coastal communities were the most neglected – socially and politically – across Kerala. Educating the female population within the communities presented its complexities. For one, it was customary within many communities that the girls not travel outside their village much once they started menstruating. S.I.S.P. worked around this challenge by forming their first team of social workers – six female volunteers – to reach out to the girls and women inside the village and educate them.

Kumari, S.I.S.P.’s secretary and who has been with the organisation for as long as Paul and Werner, vividly remembers those days.

“I joined here in 1997 as a social worker, with experience working in Eastern India. Despite coming from a middle-class background, the life and conditions of the people in the rural coastal regions shook me.” She grimly recalls her early days, marked by breaking down at the centre after the field visits.

The unavailability of proper healthcare was a serious problem in the coastal region, along with poverty. Tuberculosis was quite widespread at the time. S.I.S.P. soon started a social welfare centre to support the communities financially and to provide social administrative help (the centre supports around 200 families at present).

Child labour was rampant in Kovalam and surrounding regions, owing to their tourism status, especially amongst the migrant population. S.I.S.P. collaborated with the local law & order authorities to tackle this issue.

“Social work used to be much more politicised in Kerala in those times,” Paul says. In the early days, they used to get regular visits from local political party wings. And as anywhere else in the globe, it was hard to keep religion out for long. The organisation strictly adhered to the ideology that its efforts transcend all corners of society. Thus, even the church’s attempt to reach out to “support” their work was turned down by Paul and Werner.

Mohanan Sukumaran, the President of S.I.S.P., who joined the organisation 12 years ago with a quarter of a century of experience in rural development programmes, elaborates on this.

“I came to know of S.I.S.P. and their efforts through a friend of mine in ’97, while working with the Kerala Rural Development Department in Vizhinjam. Back then, there were several commendable initiatives by small organisations and individuals for the upliftment of the coastal communities here. But I saw that they lacked an aligned approach with the local government bodies, which would bring forth more community involvement.”

Paul was very receptive to his suggestions on FCRA registration and several structural changes the organisation could implement, that would allow them to avail the governmental schemes better. Around this time, Vizhinjam faced a dire shortage of drinking water. S.I.S.P. took up the initiative of providing drinking water to the people in the region, working alongside the Panchayat bodies.

And Then There Were… MANY!

With time, S.I.S.P. saw a steady increase in the number of students, particularly those forced to drop out of regular school. A school bus was donated to the centre by a well-wisher, enabling them to pick and drop the students from their locations. The social worker team expanded simultaneously.

The organisation was spreading its branches amongst the communities steadily, but along with that came newer operational challenges. It was tough-going financially for S.I.S.P., and shifting from one rented building to another now and then proved quite a hassle. Having their own land had become the sine qua non!

Through a collective fundraising effort by several international groups involved in similar initiatives, S.I.S.P. was able to purchase some land and fulfill an important milestone – an educational, social welfare and self-employment unit, all under one roof. Just as Peter Parker had come to accept once, with great power did indeed come great responsibilities. The organisation was actively supporting the lives of several women from the coastal communities, especially the single mothers. It was imperative to train them in self-supporting labour skills with an eye for the future.

Mereena, who heads the SEP (Self-employment Program) at S.I.S.P., had joined the centre as a social worker back in ’98. The handicrafts designing unit at the centre was headed by her when it started on a small scale about 18 years ago, and she has since been fully involved with managing the program. The stitching centres and the paper bag manufacturing units were added to the program a few years later. It was the mid-2000s by then, a decade into S.I.S.P.’s journey, and the start of something wonderful once more.

During his travels across other parts of the country, it became apparent to Paul, how the issues posed by caste framework were relatively lesser in Kerala. But like any other society, Kerala wasn’t devoid of contradictions and disparities either.

“The attitude towards skin colour here greatly puzzled me”.

It was difficult for S.I.S.P. initially to get families to allow their girls to participate in outdoor activities. The parents worried about the girls becoming darker in the sun, which would in turn affect them getting married off early!

It wasn’t always as bright as it looks now for the women’s groups, Kumari recalls. In the earlier days, there was resistance from the men in their families to even attend the programmes and sessions that S.I.S.P. conducted. Over time, that hasn’t disappeared altogether, nonetheless changed for the better. Women are more aware of the social and economic independence they can have through the self-employment program.

“Domestic violence has always been a problem, then and now. Our social workers try to give counselling and support to the affected, to the extent we can intervene,” she adds.

Paul says that the social welfare schemes in Kovalam, Vizhinjam, or coastal regions across the state for that matter, were practically nonexistent two decades ago. Since then, government policies have only evolved for the better over the years. Still, he feels the welfare schemes are inconsistent and irregular in their implementation and too obscure for the communities oftentimes.

He recalls one such recent instance involving public healthcare. S.I.S.P. had been working with the communities in providing dialysis treatment to those suffering from chronic kidney issues. Paul came across the news of a government scheme, providing free dialysis sessions to those in dire need, from low-income households. When S.I.S.P.’s social worker team reached out to the local government bodies, they were informed that the scheme was put on hold.

Similarly, Paul recalls how there had been a crackdown on plastic bags in the region a few years ago, which in turn led to a sudden shoot in the demand for their paper bags. That lasted only a few months though, and everybody was back to using plastics.

Despite Kerala boasting of inarguably the best social welfare and healthcare framework in the country, the public policies surrounding disability and disabled communities leave a lot to be desired. The unavailability of timely medical care and accessibility issues are more aggravated amongst the coastal communities.

During S.I.S.P.’s early days, Paul, who had some medical experience in Belgium before, visited and provided medical aid assistance in the coastal villages himself.

“Over the years, I have come across so many paralysed and bedridden people in these regions, for whom home is like a prison,” he says. The roads leading to their houses are often so narrow, and sometimes practically nonexistent, that even an auto has little access.

One of the first steps taken by S.I.S.P. ‘s medical volunteer team was to provide ergotherapy to the disabled community members. They also worked on making some practical changes within their homes, to aid their mobility.

The general lack of sanitation was certainly one of the main challenges for the communities here, Mohanan says, reinforcing Paul’s point. It was certainly aggravated in the COVID period, during which S.I.S.P. reached out to the people through the community health centres and the police.

“The lack of toilet facilities has been a ceaseless challenge though,” Kumari points out. A couple of decades ago, there was not a single public toilet here, forcing many of the population to use the open spaces. The women in the communities found it the most difficult, having to get up at 3 or 4 in the morning, just to carry out basic needs. S.I.S.P. worked with the Panchayat in building toilets inside several homes. Since then, public toilets have been constructed through governmental schemes from time to time, but they more often than not remain closed, Kumari adds with a touch of exasperation in her voice.

The Kids are Alright

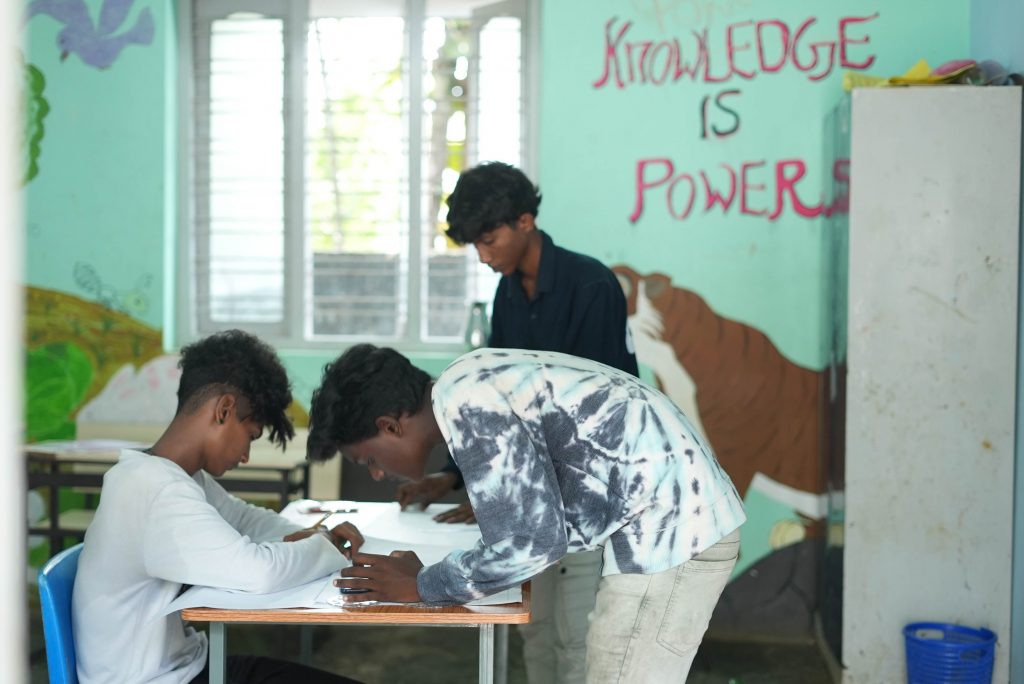

S.I.S.P. is affiliated with the Kerala Literacy Mission under the Open School Programme, holding classes for Standards. 1 to 12. The school evaluates the performance of the students at the end of each year, assessing their capability to proceed to the next Std. and to prepare them for the board exams. The students are also encouraged to rejoin a regular school with S.I.S.P. taking care of the expenses.

Quite a few of their Class 11th & 12th students are dropouts, who find it difficult to attend a school too far from their home for higher secondary education. The higher secondary classes were first introduced five years ago with just 20 students. And there wasn’t any apparent need to evaluate them because they had already cleared their 10th board exams.

“But it was baffling how many of them lacked basic knowledge of several subjects,” Paul says.

The teachers soon realised that these students were likely to fail the HSE board exams unless they worked on their skills. Thus, the BEP – Basic Educational Programme – was introduced.

S.I.S.P. has a CARE group as well – an idea that arose with the increasing number of attendees at the school who had to start their education from scratch. Many of them were too old already for primary education age in a regular school environment. The group consisted of quite a few children from migrant families, who couldn’t join the public schools due to language comprehension issues.

While a lot has changed in Kerala with regard to social development of female children, Paul observes how difficult it has always been to convince the communities and families to send their girls to schools. Yet, quite a few of their top performers over the years have been girls.

“Two of them from our first batch are working in Bangalore as engineers. And so many of our students are employed in nursing jobs across India,” he beams.

While providing the necessary framework and support to the children to seek education can pose several challenges, motivating them consistently to keep learning is more challenging, Paul feels.

One way to get the children to stay in school was to make the school more of a “learning centre” and not just a place for studying. The idea of skating, surfing and coding clubs arose from this. The students attend regular academic classes in the morning and are encouraged to pursue something non-academic at noon.

The Elite Club for Everyone

S.I.S.P.’s name has become so synonymous with its skating club locally, despite its impact in various other facets over the years. As I learned more, I realised how it was a perfect testament to S.I.S.P.’s philosophy of community engagement.

The skating club was founded by Vineeth Vijayan (34) because, in his words, “I couldn’t surf like the other kids!” That’s putting it lightly though!

When Vineeth Vijayan first came to S.I.S.P. as a 14-year-old, he was just another kid who felt out of place in the regular educational system. At S.I.S.P., he felt at ease. They had a surfing club already and when his fellow mates were showing off their skills, Vineeth could only sit and watch them with no natural talent for it.

When a friend suggested skateboarding to him, Vineeth’s interest piqued naturally. As luck would have it, he soon found a discarded skateboard from the beach, with which he started teaching himself through Youtube videos and practising on makeshift ramps. Injuries and stumbles came along galore, but only made him more determined and passionate about the sport.

His efforts didn’t go unnoticed as Paul and others saw how serious he was about skating. Besides, S.I.S.P. ’s philosophy of – “No School, No Surfing” – wasn’t possible during the monsoons in Kerala, and skating proved to be a terrific alternative. And thus, with some other organisations pitching in as well, a mini ramp was constructed on the centre’s terrace. The dimensions of this were still not ideal for beginners though, and soon enough, Vineeth organised a crowdfunding initiative to build a more suitable ramp on the ground floor.

“After that was completed, there was no looking back! We had immense support from people all around,” Vineeth says.

Thus, the first official skateboarding club in Kerala was founded by Vineeth Vijayan at Thiruvananthapuram in 2013, a fact he’s too modest to raise in our conversation until that point, but extremely proud of.

Soon, the club’s youngsters attended popular tournaments across the country, winning many of them, and getting chances to participate in other prestigious tournaments. In tandem with S.I.S.P.’s general community engagement philosophy, most of the members in the skating club were from the economically unprivileged families in the coastal communities around the region.

Vineeth can’t stop gushing about the students from S.I.S.P. who have won accolades in skateboarding. Joshan is one of the very few skaters from Kerala selected for the Asian Games to be held later this year. Vineesh S won the bronze medal and Vidya Das the gold medal, at the National Games held in Gujarat in 2022.

Only 14, Vidya is an incredible talent Vineeth says proudly. He considers her inarguably the best female athlete in the sport in the country right now.

But the gaining popularity of skating posed another conundrum to Vineeth. The club was rapidly growing in numbers, more than what he and S.I.S.P. could handle operationally and economically. Besides training, S.I.S.P. also took care of the children’s medical insurances and other expenses, including travel.

Nationally, skateboarding still comes under the RSFI (Roller Skating Federation of India). Despite all these accolades, Kerala still largely ignores the sport, Vineeth says. There are hardly any skate parks in the state, and more importantly, the Kerala Sports Council has still not recognised the sport officially. This meant that there was no academic merit awarded to the S.I.S.P. students who won medals at the highest national level.

Vineeth is understandably indignant while raising that point. “Don’t take me wrong, but there are umpteen other sporting events being approved here. So why not this?”

The general lackadaisical attitude towards the sport here also stands in the way for the skating club being affiliated by the Kerala Roller Skating Association, which comes under RSFI.

“We were told a while ago that if we could bring back 2 medals from the national games, our affiliation shall be granted. We have won as many as 5 medals since then, to no avail,” Vineeth sighs.

Without the affiliation, there’s no governmental support – economically and in other aspects – for the skating club now. While most kids who take up the sport are supported by their families, S.I.S.P. is one BIG FAMILY, taking care of everyone who’s a part of it. No child who wants to pursue the sport will be left out, Vineeth says firmly.

Despite all the silver linings and proud moments, that remains a dark cloud covering Vineeth and S.I.S.P. ’s skating dreams.

The Present is the Future and Vice Versa

The concept of education and academics has evolved so much over the years, Paul says. Previously, many children were enrolled by their families, aiming for minimal educational requirements with an eye for the future – like working in the Middle East. That has certainly changed for the better. Fishermen especially are motivated to educate themselves more to keep up with the technologically advancing world around them.

S.I.S.P. has 42 SHGs (Self-help groups) under their wing right now. It’s a member of the National NGOs Confederation through which, one of the recent initiatives was implemented. Several women from the Vizhinjam coastal communities and members of S.I.S.P. ‘s self-employment program were provided sewing machines – with half of the cost paid by them and the other half covered by the confederation.

S.I.S.P. has had good support from the local law administration over the years, particularly the Janamaithri police station. The wound care program is being consistently carried out with great success, coordinating with the local Panchayats, health inspectors and Pallium India.

There are around 45 staff at present. The number of students at the centre has come down from over 150 in the earlier years to just over 60 these days. However it’s no cause for alarm, and is indeed a sign of progress, Paul and others say.

During the first half of their journey, the number of children who were dropouts from regular schools was significantly high here, which has come down considerably over the years. While the policies aimed at bettering the public education system in Kerala have largely contributed to this change, S.I.S.P.’s share is no lesser. Paul likes to credit mainly the women’s groups working with them from within the communities. There are around 600 plus women associated with S.I.S.P. currently, motivating the people to gain education and social empowerment.

As impactful and inspiring S.I.S.P.’s journey has been all these years, the practical obstacles they had to face as a non-profit organisation have been several, from time to time. For one, Paul understands that it isn’t feasible to expect young people to consistently be motivated to do the work they do, for salaries that cannot be matched with in other sectors. But S.I.S.P. has had the fortune of having a highly motivated team at every juncture, many of them who grew up studying at the school.

As for Paul, he has been contemplating retirement, after all these years. The COVID-pandemic period, during which he didn’t visit Belgium, certainly gave a firm nudge to that thought. At 65, Paul has been going easy on himself with the daily work schedule, handing over more and more responsibilities to the others at S.I.S.P.

Learn more about S.I.S.P. here –

https://www.facebook.com/Friends.of.SISP

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1032687036742396/