By Bharath

Published: July 31, 2021 7:25 pm

While it often comes off as a cliché when you describe someone as a multifaceted personality, in Ranjini Krishnan’s case though it seems fairly reasonable to use that label. At 40, she already holds a doctorate in psychology, worked shortly as a journalist, wrote a movie script, is an entrepreneur and has produced and directed an experimental short film. Talking about her entails talking about every single one of the aforementioned elements.

Ranjini grew up in Moozhikkulam, near Angamaly in Ernakulam district, where she currently resides as well. After completing her MA in Psychology, she decided to pursue a journalism degree.

“Psychology helped me understand the mental-psychological aspects of things and journalism gave me a grasp of the socio-political sides of the same,” she recollects with a smile.

The nature of wanting to critically analyse things was always a part of her, having grown up in a supportive family structure, Ranjini says. Her father in particular, a staunch communist, encouraged the children to discuss and share their perspectives and opinions on everything.

Ranjini took up a research project at the Centre for Development Studies (CDS), Trivandrum, in 2005, where she interacted with many like-minded people and senior scholars. The project and the research collective brought about much needed clarity to her about the field of gender studies.

In 2008, she joined the Centre for the Study of Culture and Society (CSCS) in Bengaluru. Her thesis was titled “The Experience of the ‘Intimate’ in Contemporary Kerala Towards the Understanding of an Erotic Economy”, and focused on the concept of erotic economy in Kerala society.

“I wanted to inspect the phenomenon along the lines of how human desire functions through not just psychological, but also social and cultural lenses. The fear that came along with the concept of wedding night for women had to be studied through the sexual politics in our society, particularly exploring the taboo of premarital sex and the ‘myth of virginity’,” she says.

Ranjini returned to Kerala in 2010 to continue her research full-time.

The Research

“Over the course of 3 years, I interviewed around 40 women, out of which 22 interviews were transcribed in detail. They were mostly in their thirties, with one interviewee as old as 60. I took the process rather slow because I followed an in-depth, but unstructured form of interviewing,” she says.

“I kept my recorder on and just asked them to talk about their concept of the ‘first night’. The individuals went about it in different ways, some even starting with the experiences of others. But as we went deeper into the conversation, they eventually opened up about their own wedding night.”

Ranjini remembers that the interviews stretched from half an hour to 2.5 hours, with one in particular even lasting 4 hours, at the end of which she herself was close to tears.

She started her thesis citing the Phulmoni Dasi case from the 19th century – the first reported case of marital rape in India. Moving on to the Kerala society, Ranjini inspected the historical narratives of marriage and family structures in our culture, and how the idea of consent has changed (or not) over time.

“Without proper personhood and fair human rights, the idea of consent isn’t possible,” Ranjini says, adding that even the reformists in the earlier times were only fixated on abolishing the concepts like ‘Thali Kettu Kalyanam’. While there were a multitude of aspects to that, it also had undertones of establishing the patriarchy stronger.

“The thesis further explored the sexual culture of Kerala, on ‘the making and managing of the virgin bride’. I examined the visual field created around a fully adorned bride, right from how the ad hoardings placed on the roadside to the vaginal tightening cream ad influenced our minds,” she explains further.

Ranjini analysed the Sister Abhaya murder case to discuss how the ‘virgin concept’ worked in the legal course in contemporary times and delved into Kerala’s cultural-historical narratives, like – ‘Marumakkathayam & Makkathayam’, contractual marriage, property relations, etc. to address the popular psychological discourse impacting the idea of the first night and the actions it prescribed.

She rounded off with a chapter containing the interviews themselves, titled – ‘Daughters of Sheherazade’ – and concluded by talking about what exactly the erotic economy meant.

The Revelations

“I would say…that the stories I heard, undercut all distinctions of class, caste, religion, region and age in the society,” Ranjini muses. “I think the most common and horrifying aspect was the complete rejection of the desire to be heard.”

There’s one incident that she recalls in particular:

“I went to interview someone at an office once, and a woman – the office assistant – came to know about my thesis. While leaving the place, she approached me and said she would like to talk sometime. I agreed and fixed a date for the following week.”

“During our meeting, she came off as a really cheerful person. She started talking about her family and other stuff, but nothing related to my topic. I didn’t push the question at her either.”

“After 40 minutes or so, I felt she may not be comfortable opening up to me about her deep personal experience(s). Not wanting to pressurise her, I prepared to leave, promising to keep in touch.”

“And then suddenly she raised the matter…”

The woman talked for more than an hour and a half about her experiences, which included marital rape. “By that point of time in my research I had heard so many accounts that I had more or less become numb to it,” she adds solemnly.

Ranjini says that the woman’s story was quite typical of what she had heard so far during the research. The (woman’s) husband had forced himself on her on the wedding night, even after she rejected his advances. She recollected not eating anything the whole wedding day, in the rush and anxiety. And so, after an entire day of being starved and nervous, she was raped during her ‘first night’.

“The woman told me – ‘I had cousins and relatives whom I could have talked to, but I needed someone like a sister to talk about this’. And it pained me that she was carrying this burden all these years,” Ranjini says, adding, “And even after sharing this, she vaguely carried a feeling still that she couldn’t be an ideal bride that night, which made me even sadder.”

She recounts, “Almost all the women I interviewed were physically forced itself into the act. There were those who felt bitterness about it in the present. Some felt they couldn’t ‘love’ their husbands truly after the incident(s). They respected them, ‘liked’ them, but couldn’t love them. There was one woman who told me she felt like she was being pushed into a lodge room.”

The birth of Daughters of Scheherazade

Even after submitting her thesis and receiving her PhD, Ranjini sensed that, “The people, and their stories, hadn’t left my mind.” Although she was quite occupied with her family and entrepreneurial venture, she felt she needed to do something more to narrate those experiences.

This prompted her to apply for a filmmaking fund in India Foundation for Arts (IFA), Bangalore, in 2018. She wrote to the foundation mentioning her thesis, and on their suggestion submitted a proposal containing a few scenes for an experimental short film she had in mind.

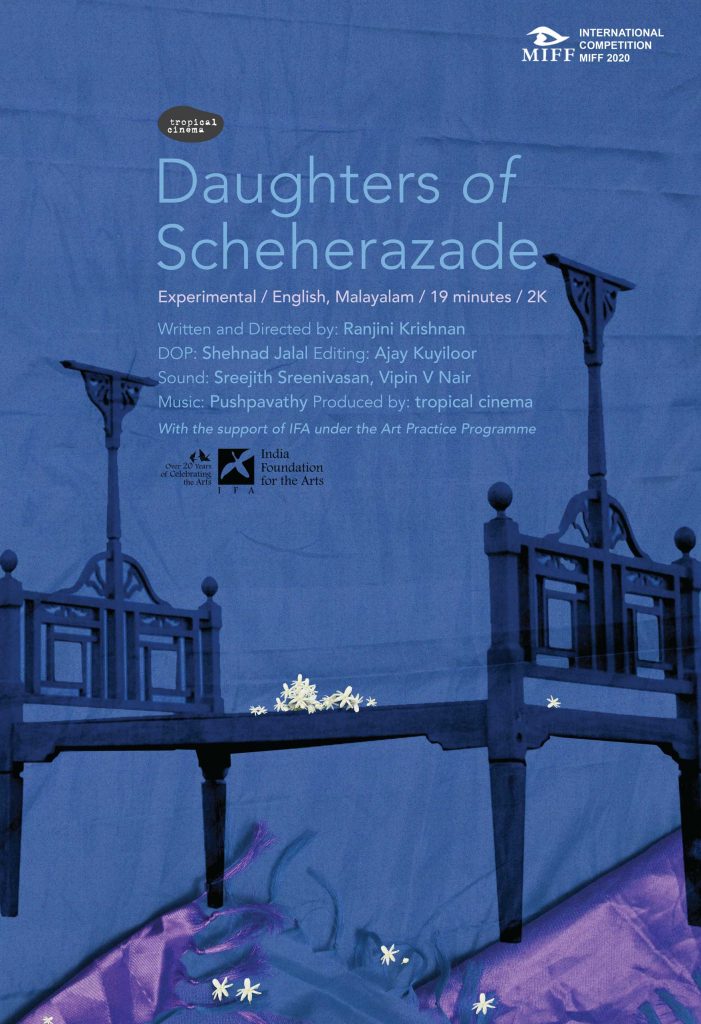

The foundation’s response was positive and she received the “Art Practice Grant”, paving the way for the birth of Daughters of Scheherazade.

“Through my film, I wanted to resume from where I had left off in my research and explore the concept of the wedding (first) night, considered as the pinnacle of romantic intimacy, but that which also held the potential of danger. The state of the experience being ‘neither intimacy, nor violence’,” Ranjini reflects on it.

She had decided before itself that she would use one of A.R. Rahman’s songs as the background score and ended up choosing Yaro Yarodi because, “It symbolised human longing”. She used a non-linear narrative for the film and attempted to portray the story of ‘not just a single bride’ through it. Ranjini explains that it included a hopeful bride, an excited bride and a violated bride all at the same time, but combining to represent a singular form ultimately.

“I wanted to place the bride in an amorous encounter between pain and pleasure. Between the historical and the lived. Between the mind and the body. One may feel that her mind was recounting the story and the body was violated. And at other times, the body desires for the touch, the affection, but the mind may have the memory of it being violated once,” Ranjini narrates.

The production was carried out by Tropical Cinema, co-founded by Ranjini and her husband, Manoj. While the shoot was completed by 2018 itself, the post-production took them a little more time. Daughters of Scheherazade was first screened in November’ 2019 at #PastForward, an IFA (India Foundation for the Arts) festival, held in Bangalore. Most recently, the film was screened at the Kerala Museum, Kochi, in March’ 2021.

The Journey to BodyTree

In 2011, Ranjini and Manoj were working on a documentary project titled, A Pestering Journey. The feature covered two of the major pesticide disasters to have happened in post-independent India – the Endosulfan tragedy in Kasargod, Kerala and the story of the ‘cancer train’ between Bathinda in Punjab and Bikaner in Rajasthan. It explored questions like, ‘What and who was a pest?’ and ‘How did our society legitimise some form of killings and not some others?’. The stories that they came across during the research and making of the project shook both of them to the core.

It was around this time that Ranjini became pregnant with her son, whom she gave birth to in 2013.

“But by now I was quite obsessed thinking about the various chemicals used in baby products, their carcinogenic factors and so on,” Ranjini says.

She used many natural products instead of the commercial soaps in the market, but due to several reasons, none of them fully convinced her. During that time, Ranjini chanced upon the process of natural soapmaking in a parenting ideas Facebook group she was part of.

Although her first couple of attempts weren’t a complete success, she got the hang of it by her third batch. She started using these soaps at their home as well as gifting it to her friends. “I was spending quite a bit on the ingredients, but soapmaking had become a therapeutic activity for me. It helped me a lot in dealing with the stress associated with my research also,” Ranjini looks back on it.

At one point, she had over 300 soaps with her and realised that she couldn’t just gift away that many to friends and relatives. This paved the way for the idea of BodyTree in her mind.

Moving Forward…

By 2016, she had received her PhD and was looking at career choices. Yet, Ranjini was unenthusiastic about the obvious choice of an academic job. Her interests lay in research and further exploring the field of Critical Psychology.

“Critical psychology borrows less from the conventional theories of the West and focusses more on the social, cultural and political aspects of each individual society, to address corresponding psychological phenomena. My idea of psychology is emancipatory. Unless we start examining psychology in relation with aspects like gender, caste and class, as well as with respect to our social structure, we won’t make much progress,” Ranjini elaborates.

Through her research and the experimental film, Ranjini says that she was attempting to convey the idea – the ‘Intimate is Extimate’. She wanted to show how the factors like society, community, state and legality interfered in a space (like the bedroom) which was considered to be the most intimate, and how someone’s “voice” became critical in a space like that.

In a heterosexual relationship in our societies, in the beginning itself there is an apparent power imbalance, Ranjini feels. The conclusion of her thesis was about the erotic economy; about ‘First night as a site of erotic danger’ and to what extent women were aware of this, the knowledge a patriarchal society imparted to them and how they navigated all of that.

“We need to democratise intimate relationships and make them more loving and understanding, so that an individual’s desire, pleasure and carnality are valued. Instead, we narrow down the whole concept to confined spaces. The wedding chamber later literally becomes the ‘master bedroom’, unironically. This is the start of the process that chains and undermines the sexual and reproductive labour of married women,” Ranjini points out.

“In essence, we have to be more democratic in concepts, and spaces, where we never considered the importance of the same before. We need to confound idioms of speech; understand that it’s not just about democratising spaces of love but also the significance of love in democratising societies,” she concludes.